The eve of Shavuot is one of the most awesome dates on the Jewish calendar. Imagine yourself going back in time and standing again at Sinai as our forbears did three millennia ago. According to the Talmud, the soul of every Jew was at Sinai, so return now to re-experience that event.

Close your eyes and rock a little bit on your feet. Remember that you have fasted for 3 days, have purified yourself and are now waiting at the foot of the mountain with a mixture of fear and awe. Suddenly, the ground starts to tremble under your feet. The air crackles around you and you lift up your arms to the Heavens. The Heavens are filled with thunder and lightning. From the top of the mountain, you hear the Voice which fills all the space around you:

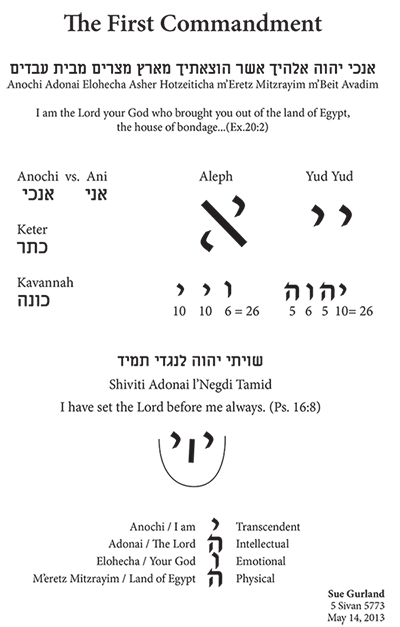

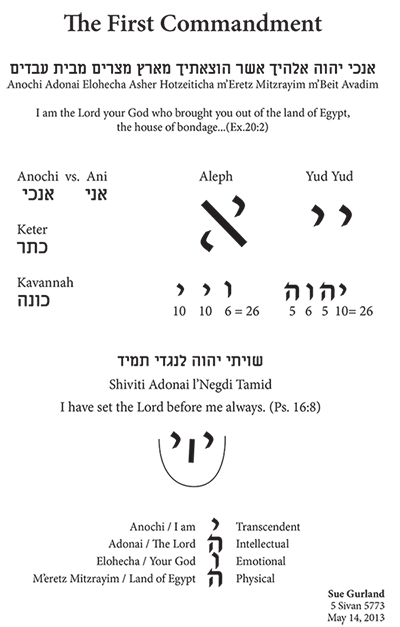

Anochi Adonai Elohecha, asher hotzeticha mei’eretz mitzrayim mi’bait avadim…

I am the Lord your God who took you out of the land of Egypt, the house of bondage…

Feel in your body your connection to that overwhelming experience that our ancestors witnessed on Shavuot. Midrash tells us that it was so literally earth-shaking that the people fled after the second utterance, begging to hear the rest from Moses, unable to stand in the Divine presence any longer.

Now, sit down quietly. What do you remember of the first commandment? While the first commandment makes explicit the connection between Passover and Shavuot…we were taken out of Egypt and brought to this holy mountain 50 days later to receive the covenant… what most of us remember of the first commandment are the first three words, “ Anochi Adonai Elochecha, “ “I am the Lord your G-d.”

The Ten Commandments are said to contain all 613 mitzvot. In fact, there are 620 letters in the 10 Commandments, which are said to stand for the 613 mitzvot plus the 7 Noahide laws. It is also said that all the commandments are contained in the first two (one positive and one negative) and that the first two commandments are contained in the first one. The first commandment is then contained in the first word, Anochi, and the first word is contained in the first letter, Aleph. This reductive analysis begs further exploration.

The first question that comes to mind when we read this commandment in parashat Yitro is, “Why Anochi?” “Why not the often-used word, Ani, to mean I?” In fact, Ani appears 112 times in the Torah, while Anochi appears just a handful of times, and each time it refers to something concealed.

Anochi, in fact, comes from the Egyptian language, so it would have been understandable to the people. Since it is an unusual usage, it grabs your attention. Anochi places a strong emphasis on the individual; Ani, on the other hand, emphasizes the action. Anochi says, “I” am the Lord your God.

The difference in spelling between Ani and Anochi is the addition of a “chaf” in Anochi. This is the same letter that appears in the word “Keter” which means “crown” and is the first sephira of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, denoting God’s kingship, the first Divine emanation from the Heavens into this world. Kaf also begins the word “kavannah” which relates to one’s intention. And the “kavannah” of the first commandment establishes the personal connection between God and the Israelites.

This is further reinforced by the grammar, because the pronoun suffixes of “elohecha” and “hotzeticha” both refer to “you” in the second person singular. This is an unexpected usage, since G-d is addressing the whole multitude gathered at the foot of the mountain. The message that the grammar emphasizes is that this is a personal G-d who is making a personal covenant with each individual standing at Sinai—then and now. This is not the impersonal G-d who created the Universe. This is the personal G-d who took us out of the Land of Egypt, the house of bondage. One unique G-d making a connection to each unique individual.

Next, Focus on the first letter, Aleph. There’s a sweet midrash that says that for 26 generations, the letter Aleph complained to G-d, “I’m the first letter of your letters, yet you didn’t create the world with me.” “Don’t worry,” said G-d. “Tomorrow when I come to give My Torah at Sinai the first word I say will begin with you.”

The Aleph is made up of 2 yuds and a vav. The diagonal vav has been likened to Jacob’s ladder, which connects the upper and lower realms of Heaven and Earth, represented by the two yuds. Looking at the letter in that way, gives a physical representation of the verse from the Zohar, “As Above, So Below.” We also know that the double yud is used as a symbol for G-d’s name, Adonai.

Taking this a step further, by deconstructing Aleph into its parts (2 yuds and a vav) the gemmatria or numerology of Aleph becomes 26, which is the same as the gemmatria of the 4-letter name of G-d,

Y-H-V-H. If we draw the 2 yuds with the vav vertically between them, it’s apparent that every face carries an aleph on it. This calls to mind the verse from Psalms which appears, “Shiviti Adonai l’Negdi Tamid”, “I keep G-d before me always.” One of the ways we keep G-d before us is by carrying the aleph on our faces. It gives new meaning to “b’tzelem Elohim,” that we were created in the image of G-d. And it gets even better…

Since the gemattria of Aleph is the same as that of Y-H-V-H, if we write the Y-H-V-H vertically, you can see that we carry the 4-letter name of G-d on our bodies. The yud forms the head; the upper hay, the arms; the vav, the torso; and the lower hay, the legs. In addition, these 4 letters correspond to the 4 levels of soul, starting with the yud—the transcendent; the hay, the intellect; the vav, the emotions; and the lower hay, the physical. What’s more, if you write the beginning of the first commandment vertically, you see that the words also correspond to the four levels of the soul: I am—transcendent; the Lord—intellect; your G-d—personal/emotional; who brought you out of the Land of Egypt—physical.

Getting back to the letter aleph, it is the first letter of many important words in our tradition: Elohim; Adam; Avraham, emet (truth), ahavah (love) ayin (nothingness) and echad , meaning “one”. One is also the gemmatria of the letter aleph, since it is the first letter of the alphabet. Midrash teaches that G-d addressed the aleph, saying it stands at the head of the aleph-beit like a king. “You are One, I am One and the Torah is One,” says G-d.

The aleph itself makes no sound, but communicates volumes. It is said to be the sound you don’t hear before every utterance when you speak a word in awe. Aleph makes no sound, but gives birth to the entire aleph-beit. Everything emanates from the stillness, from the silence. In contrast to the thunder and lightning of revelation, there is a midrash that says:

When the Holy One gave the Torah, no bird screeched, no fowl flew, no ox bellowed, none of the ofanim (angels) flapped a wing. The seraphim did not say “Holy, holy, holy,” the sea did not roar, none of the creatures uttered a sound. Throughout the whole world there was only a deafening silence as the Voice went forth, “I am the Lord your G-d.”

I was very moved when I read that, because in my own personal prayer experience, I’ve noticed that at the end of the Amidah, where we insert our personal prayers, I suddenly get very still. However much I’ve been swaying or bowing or otherwise moving, at the moment I close my eyes and go inward, everything stops and I get very quiet. From this place of stillness, I can then reach toward the Divine. This recalls a line from psalms which says, referring to G-d, “To you, silence is praise.”

Finally, there is a concept from Kabbalah, which, by the way, means to receive. The Kabbalists tell us that G-d created the world by contracting G-d’s self to make space for something new to appear. In the first commandment, we can trace that contraction all the way back to the first letter, aleph, the soundless breath from which the covenant arises and expands to fill our whole world.

As you stand tomorrow to hear those words anew, quiet yourself inside and find that space in your own body, in your own soul, where you can receive this covenant and re-experience the revelation at Sinai:

Anochi Adonai Elohecha….